Field Notes, No. 2: An Illustrated Overview of Budae-Jjigae (부대찌개)

A stew born out of necessity

Field Notes is an illustrated column exploring the ever-changing landscape of cross-cultural cuisine. Here, we uncover how historical and cultural encounters (e.g. via migration, trade, colonialism) have given rise to unique culinary phenomena—creating dynamic intersections where diverse food cultures blend and evolve. Unless specified, all illustrations are lovingly crafted by Shayne herself. You can check out TOD’s archive of past stories here.

In a hot, bubbling pot of spicy, fiery-red, umami-laden broth is where the past and present collide, and what was once a stew born of scarcity and survival now represents a blending of cultures. Budae-jjigae, also known as “army stew,” is much more than a staple in Korean cuisine, it’s a meal that emerged out of necessity in the time of the Korean War incorporating ingredients from the East and the West—and has since then transformed into a comforting, communal meal truly representative of resilience, resourcefulness, and the blending of different food traditions.

Our story begins in the aftermath of the Korean War (1950-1953), a time of severe food scarcity and economic hardship in South Korea. Civilians lived off surplus food rations from the U.S. military, including items like Spam, canned beans, and hot dogs. These ingredients certainly weren’t native to their cuisine, but Koreans had to make do since they were shelf-stable and an essential source of nutrition. (Since then, however, Spam has evolved into a notable ingredient in Korean foodways—a great source of protein in a bowl of ramyeon, for example, or as filling in gimbap).

Koreans began to incorporate these military rations into their meals, most notably jjigae (stew)—the result of which became a creatively improvised dish that truly embodies a melding of Korean flavors and Western ingredients. Its origins are said to be in Uijeongbu, a mountainous city 14 miles north of Seoul with the largest cluster of U.S. army bases. (Today, you can take a stroll down “Budae-Jjigae Street,” a line-up of more than 20 restaurants with their own version of the eponymous stew—the most famous of them being Odeng Sikdang, a humble food-stand-turned-restaurant credited with being the first to sell budae-jjigae. Legend has it that its founder, the late Heo Gi-Suk, used to stir-fry fish cakes (odeng) with any canned meat salvaged from the nearby army base when a customer suggested she turn the meats into a spicy stew to eat with rice).

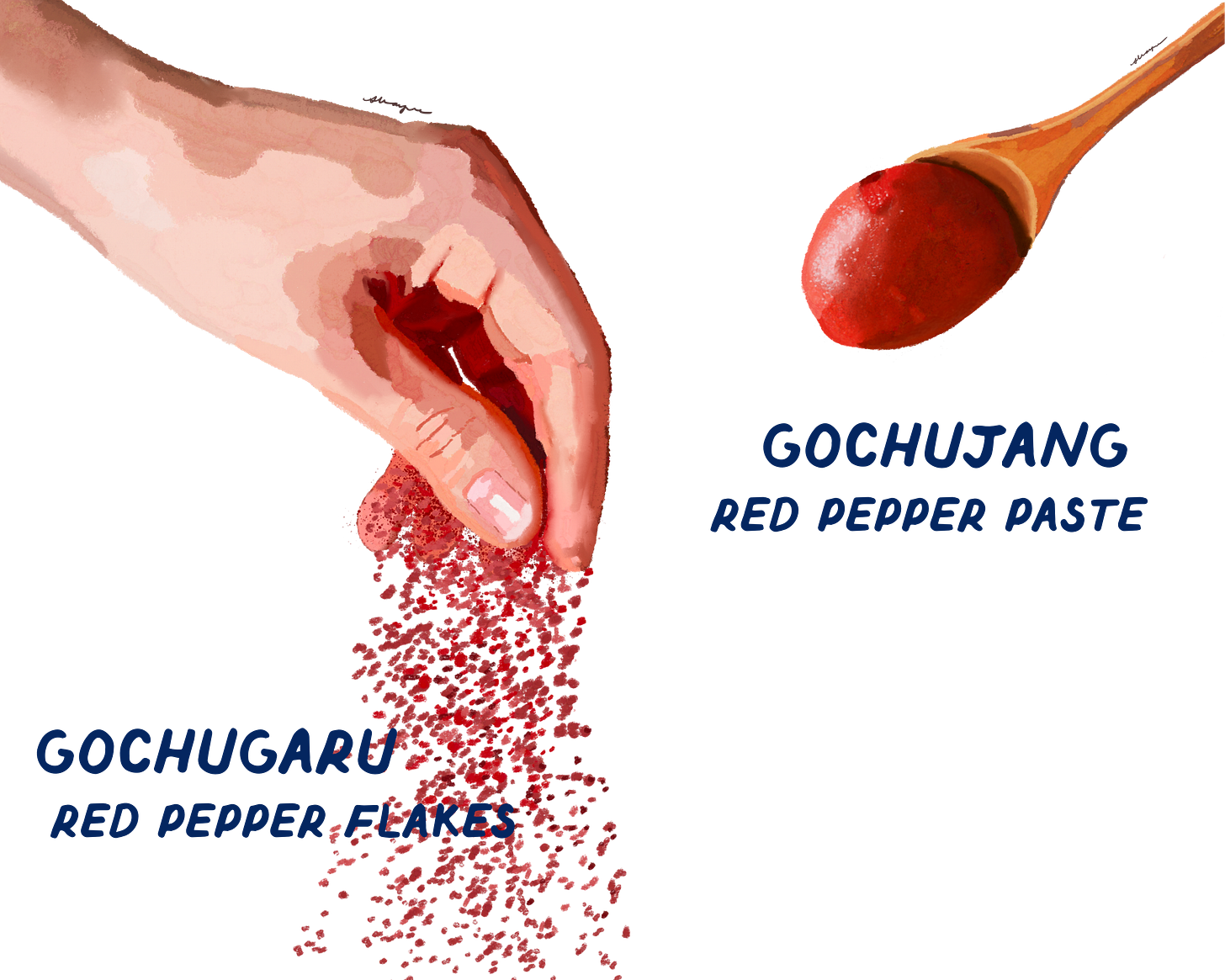

At its core, budae-jjigae’s base comprises anchovy stock flavored with a seasoning mixture of sugar, garlic, and other seasonings like soy sauce and fish sauce. What gives the stew its heat and iconic fiery-red color, though, is red pepper paste (gochujang) and red pepper flakes (gochugaru).

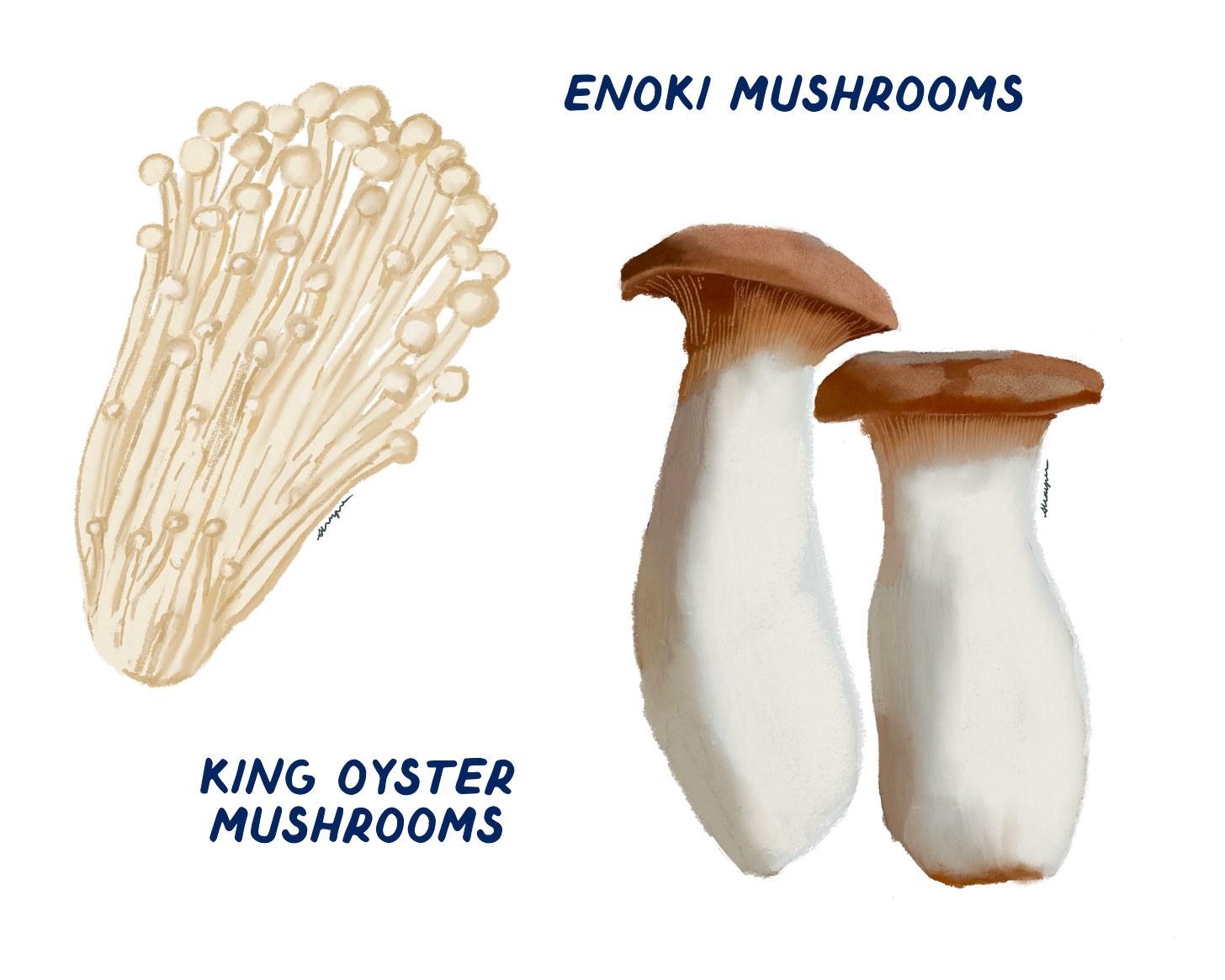

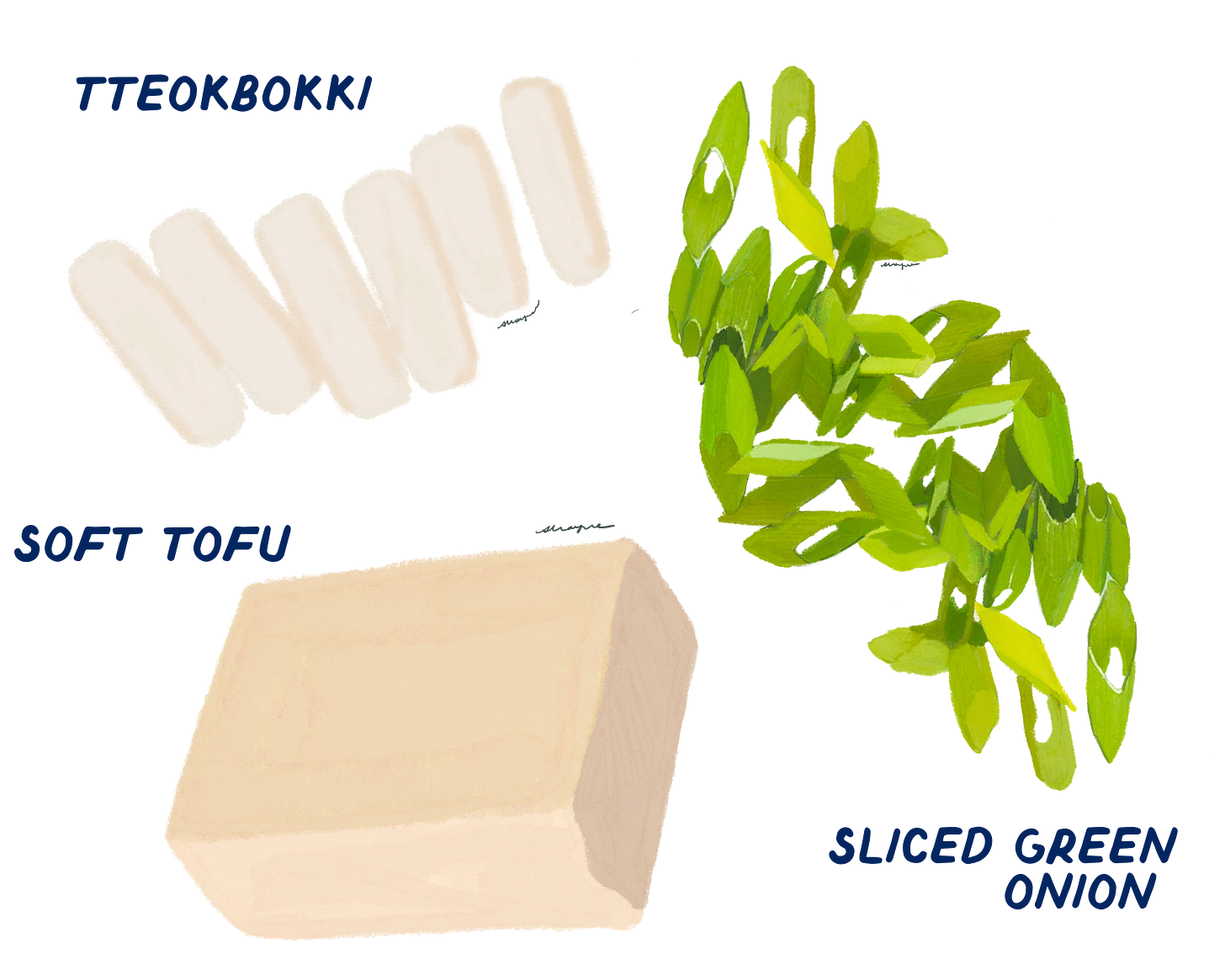

Still, budae-jjjigae is very much a choose-your-own-adventure kind of dish. Maangchi’s take, for example, incorporates baked beans and thick slices of Polish sausage, while Eric Kim’s version opts for maple breakfast sausage links to lend a hint of sweetness in tandem with Italian sausage for its savory notes of fennel. The beauty of this stew really does lie in its adaptability; Spam and sausages are traditional, but great additions include mushrooms, rice cakes, fish cakes, other types of vegetables like cabbage or radish, a bundle of sweet potato noodles, or a block of ramyeon—and don’t forget a slice or two of American cheese to melt over the top. Served with rice and/or a bottle of ice-cold soju, tucking into a steaming pot budae-jjigae becomes a communal experience with friends and family.

Though budae-jjigae originated as a practical solution to food shortages, it quickly became a longstanding symbol of resilience and resourcefulness, of the Korean people’s ability to make do with what they had. It’s a dish with ghosts, of course, particularly for the older generation—an artifact of wartime scarcity and a reminder of an incredibly traumatic event in history. Transforming military rations into a nourishing, comforting meal, however, is an incredible testament to their ingenuity in an era of struggle and adversity; it highlights their way of both adopting and adapting foreign influences without compromising its culinary heritage. This stew as a whole is a marriage of foreign and domestic ingredients—truly representative of their incredible ability to adapt and transform, calling on different influences to create something that is still oh so uniquely Korean.