Kiera Wright-Ruiz on the Half Latinx Experience

+ more on cooking, eating, and living as a food writer in Tokyo

**Just as a heads up: some of the links in this post are affiliate links, meaning I’ll earn a small commission at no extra cost to you if you decide to purchase the amazing books, ingredients, etc. through them. Thank you ever so much in advance for your support of this newsletter ❤️

Despite being half Latinx and half Asian, Kiera Wright-Ruiz’s journey in understanding her identity has been anything but straightforward. Though mixed-race children or children of immigrants often grow up cognizant of their family’s respective culture and traditions, Kiera’s childhood was, comparatively, a bit more complicated. Different people had stepped in to play the role of caretaker throughout her life—if not her Ecuadorian father or Korean mother, then her Cuban foster parents and, later, her Mexican grandmother. Each caretaker and family member hailed from a different part of Latin America, imparting invaluable wisdom from their respective foodways and cultures that ultimately shaped Kiera’s view of Latinx food and identity—not to mention, her understanding of who she is.

All of those experiences have since been chronicled in Kiera’s second book (yet first full-fledged cookbook!), “My (Half) Latinx Kitchen,” featuring 100 recipes uniquely organized by different eras in her life. She’ll take you through the Ecuadorian classics she ate as a child, ceviche de camarón and seco de pollo included. You’ll learn about her grandmother’s pozole rojo and horchata, as well as the ropa vieja and picadillo that her Cuban foster parents served (don’t forget to make extra to stuff some papas rellenas!) Of course, she covers what working as a food writer, recipe developer and content creator in Tokyo as an adult is like—and how elements of her Latinx heritage seep into Japanese favorites à la hojicha tres leches cake, or adobo mushroom okonomiyaki quesadillas topped with aonori, beni shoga, and lashings of Kewpie mayonnaise.

Accompanying the recipes are personal essays from Kiera reminiscing and reflecting on over twenty years’ worth of memories—how tamale soup helped bring her family together again after being separated in foster care, her brief chonga phase in middle school, and how bringing relatives to Medieval Times became a beloved, all-American tradition. (Dare we say that it tops Disney World as “The Happiest Place on Earth?”)

Everyone, please welcome Kiera to the “That One Dish” stand. This Friday, paid subscribers are getting a recipe from her cookbook—so be sure to look out for that in your inbox. In the meantime, I hope everyone has a great rest of the week.

On that note: I’m incredibly grateful for all my readers, but if you’ve been enjoying this newsletter so far, I’d appreciate your consideration in upgrading to a paid subscription. For just $5/month or $50/year, you get extra recipes and fun tidbits of supplemental content sent out on Fridays. In other words, it’s your support that keeps this one-woman editorial operation running. Thank you, thank you in advance!!

This cookbook is a deeply personal chronicle of where you come from and how that’s shown in your food—but what made you want to put pen to paper and actually create an entire book about this?

“I was working at The New York Times when I got this idea. I used to be a social editor for their cooking team, and there I was getting back into recipe development and thinking a lot about food identity stories. Seeing what cookbooks were coming out, I realized that a lot of Latin American cookbooks were very precious about the cuisine; it felt like Latin American food was only presented in one way, and it didn’t reflect how I grew up or what I identified with. Even now, there are so few books written from the perspective of someone of more than one ethnicity—when, of course, there are millions and millions of people out there like that. It didn’t feel like a lot of the stuff I was seeing out in food writing was representative of those people. I thought there could be an opportunity for me to tell this story.”

How do you feel like your relationship with your identity and multicultural background evolved during the whole process of making this book?

“In so many ways, it reaffirms where I’m coming from. Writing a book about culture and my identity, some people might expect to arrive at the end and see me experience this epiphany, this ‘aha’ moment—but that’s never happened for me. I think that’s totally okay, and I feel very comfortable that I didn’t. This book is a reflection of where I am and who I am until this point. I wanted to challenge people’s notion of how someone learns about culture. My story is all about how I’ve learned about food, my identity, the history of Ecuador, and different parts of Latin America at large in a very non-linear, non-traditional way. Those paths exist and are worthy of being in a cookbook, and are also just worthy of discussion on a larger platform.”

How would you sum up how you use food to express and explore who you are?

“For me, food has always been a gateway for me to learn more about history, whether it’s my own ethnicity through Korea or Ecuador and learning more about what’s happened in those countries, or about the indigenous people from there, and learning more about the regions at large. Food is such an inviting way to, of course, hang out with friends and connect with other people, but it’s also acted as this interest point into looking further—beyond what I see. The foods I enjoy the most are often ones where I feel like I’m eating a plate of history. It’s been really interesting and exciting to see how foods are reflective of these deeper stories, places, and people.”

Your book is full of deeply personal essays and thoughts. Were there any that were easier or harder to write about? How did you go about organizing years of those experiences into chapters and sections in a book?

“For a book like this, it’s so much about culture; it’s almost as much about culture as it is about food. The two are obviously intermingled, but I have a lot of essays that have nothing to do with food in it. It was really important for me to have that because, it can be a bit too narrow viewing my culture and identity through just food—and while it is a huge component, it’s definitely not the only way I’ve learned to embrace my Latinx heritage. I have an essay in there about being a chonga, a phase I had when I was in middle school where I fully leaned into my Ecuadorian side in spite of rejecting and hiding my Korean side from people. That story is so important, it’s a journey of being able to feel comfortable with who I am because I was so uncomfortable about it at a certain point. I also wanted to make sure there was a mix of essays that were about the joyful moments of life in addition to the hard ones. That’s why you’ll see an essay about how we went to Medieval Times when my grandma’s family came to the U.S. for the first time, and how I think that’s the perfect way to experience America. Hopefully it feels like a true slice of life for folks, and it’s not just a book of 100 recipes.”

What first compelled you to move abroad? And why Tokyo?

“I wanted to leave the U.S. because I really wanted to explore a different country on my own terms. As a child, I’d go to Mexico to visit my grandma’s family—but I was, you know, a child, so it’s not the same thing. When I was in high school, I was able to go to Europe on the first time for a longer trip, and was able to have fun and explore. It really opened my eyes to the fact that I don’t have to live in the U.S. for my whole life. I can have a different life somewhere else if I wanted to. I realized that I could feel differently about who I am somewhere else. I think of this ‘heavy backpack’ I wear in the U.S. because of my ‘otherness.’ Moving to Tokyo, it’s the first time in my life where I’ve been able to take it off and really feel a lightness I haven’t been able to experience before. It’s very different from just traveling.

Tokyo is just so wonderful. It’s the biggest city in the world—based on population. I feel very inspired here. It has everything I love about big cities, and I’m definitely a city girl. It’s just a really clean, efficient, and safe place to live. I’m always very aware of the privileges I have moving to Japan; the way I live here is very different from that of most people. I still make [American dollars], I came here with an established career, I don’t have to work in a Japanese company. I have a lot of different privileges that let me live here in a very specific way.”

What does a day of eating normally look like for you in Tokyo?

“Lately, I’ve been eating a lot of savory dashi oatmeal. Living in Japan, I always have bonito flakes and kombu on the ready, so I’ll tie up the flakes in some cheesecloth and put that and a piece of kombu into the water of my savory oats. I add a little bit of salt to taste, some sesame oil. I’ll sometimes add spinach to it and it wilts in the heat, then I’ll top it with sliced cherry tomatoes and a soft boiled egg. I’ll put a finishing soy sauce over the cherry tomatoes, and it’s just delicious and very umami-packed. I’ve been making that a lot for breakfast.

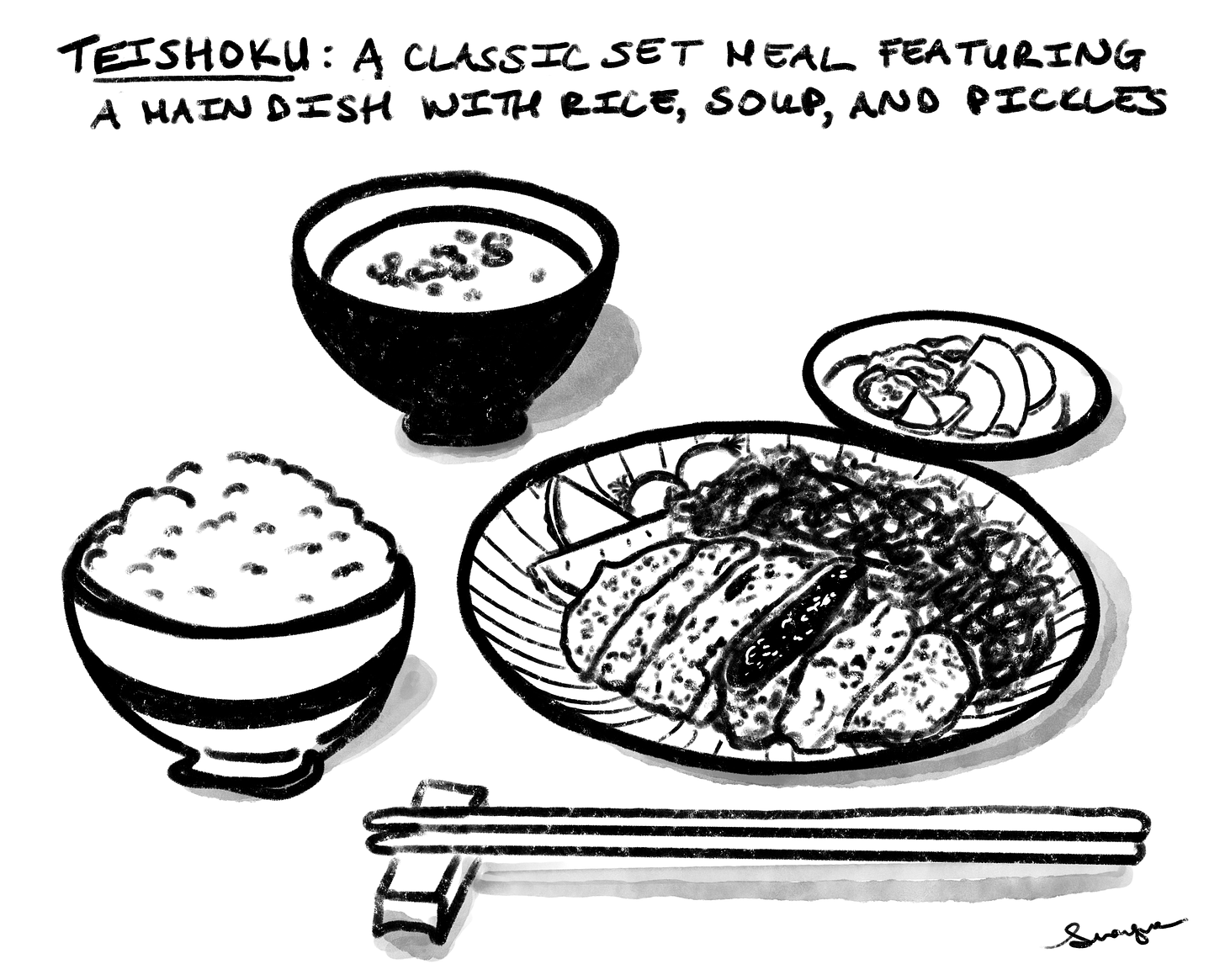

For lunch, one of my favorite things to do is to get a teishoku, which is a set lunch. Usually at the teishoku place I go to, there’ll be ginger fried pork with a little rice, some Japanese pickled veggies, and miso soup. It can vary, but that’s a pretty standard one.

For dinner? Tomorrow, for example, I’m gonna go to this really great pizza place called Pizza Studio Tamaki (PST). In my opinion, it’s the best pizza in Tokyo. Last time I went there, they had a really wonderful white sauce pizza with scallops on top. It’s really great.”

Is there any dish in particular you make that's reflective of your multicultural background, your current environment, and/or all the other places you've lived? I’m really curious if you ever see Japanese foodways and your Latinx background come together in what you eat or how you cook specifically?

“Once I moved to Japan, my cooking inherently changed—mostly because I’m in a different country. I don’t think about how I make [a given] recipe more Asian, how do I make it feel more Japanese. It’s not even about that. It’s just, like, this is the grocery store I’m shopping at and this is what I can find right now to fit, say, an Ecuadorian stew I’m trying to make. I have a recipe in my book for a vegan guatita, which is a Ecuadorian peanut stew that’s usually made with blended sofrito and tripe—but I actually started opting for maitake mushrooms instead because I just don’t eat meat all the time at my house.

Something I’ve also been making a lot that’s much more reflective of my ‘American in Japan’ side is barbecue tofu. You can’t get pre-made barbecue sauce in grocery stores [in Tokyo], so I’ll make a batch of barbecue sauce at home and put it in my Daiso squeeze bottle. I’ll crisp up firm tofu in my microwave oven, add the barbecue sauce so it gets nice, brown, and tacky just as barbecue chicken would, and serve that over a mix of rice and toasted quinoa. Then maybe honey-roasted carrots and a salad. I’ll make a dressing for it, sometimes with roasted sesame paste as a base, so it’s definitely a fusion of American and Japanese sides as well as a reflection of what I actually eat every day.”

Responses have been edited and condensed for clarity.